We Used To Just Walk Outside

Part I: The Silence of the Street – What Happened to Community?

There is a silence that has descended upon the modern neighbourhood. If you are of a certain age, you know the sound that is missing. It is the sound of unsupervised chaos. It is the sound of cricket balls hitting garage doors, of bicycles engaging doing dangerous things on steep driveways, and the unorganised roaming of children who had been told to leave the house and not return until the streetlights came on.

We remember when social networking meant sitting and waiting for something to happen. But these days, standing on a front porch in a suburb of Sydney or for that matter Seattle, or Southampton, you can feel like the sole survivor of a neutron bomb. The houses are pristine (mostly). The lawns are manicured (mostly). But the people are gone except for the occasional power walker roaming the neighbourhood.

Where are they? They are inside, of course. We are inside. We have retreated. It turns out that while we were busy digitising our lives, we accidentally ruined the communities that we all took for granted. It has been happening for some time, but since 2012 its been getting increasingly worse, a year that weirdly aligns with mobile internet becoming widespread, since then the time we spend with others has fallen off a cliff. We have traded the friction of the real world for the efficiency of the screen and in the process have forgotten how to be neighbours and a community.

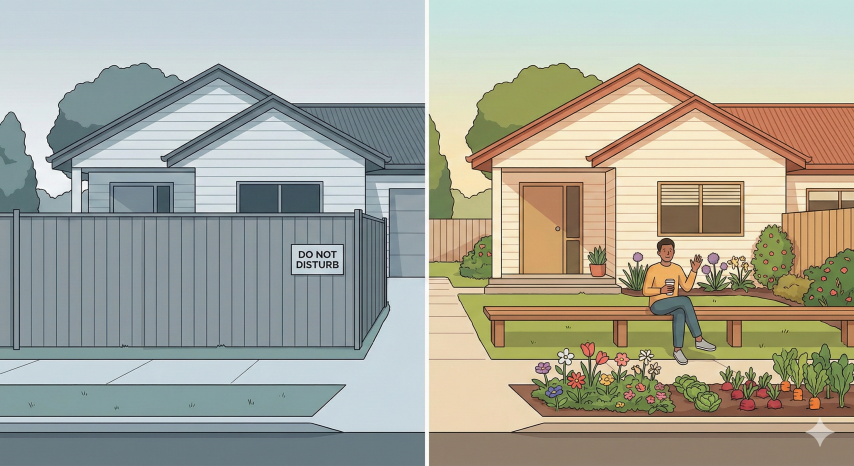

It is not just that we are busy as we always have been. It is that the whole setup of our lives has changed. In the 70s, when many of us were born, the front yard was the "middle ground" between the privacy of the home and the public drama of the street. You sat. You saw. You waved. It was verification that you existed. But then things moved to the back deck. Fences were built. We installed air conditioning and attached garages. We designed our homes to be castle of solitude where we just drove in, shut the door, and never have to suffer the awkward small talk again!

This was progress, we thought or we told ourselves. It was the ultimate luxury to buy your way out of needing other people, something probably taught by the selfish Baby Boomers before us. Nowadays, if you need sugar, you don't knock on a door, you order it on an app. If you need to know if the neighbourhood is safe, you don't ask the lady across the road; you check Facebook or Google. We replaced community with transactions.

The result is a situation where we claim we value community. We say we want to know our neighbours. Yet our actual behaviour is that we will do everything to avoid them. We operate under the illusion where we are convinced that strangers want to be left alone and that we are annoying them by intruding. We walk down the street with headphones on, normally staring at a device and this gives off the vibe of "Do Not Disturb." We have become a mystery to the people living twenty feet away.

It is worse for the kids. We grew up with the ability to roam for miles. We could walk to school, to the shops, to the friend down the road. Today, kids we don't let kids roam how dangerous is that! Yet the reality is Western society is much safer now than in the 1970s. Crime is lower. Accidents are fewer. Yet we live like we are terrified. We have let the endless news cycle and scary Facebook posts convince us that the world outside is too scary. This has resulted in us keeping kids inside, driving them to organised playdates or activities and the result is that the streets have turned into nothing more than a place for cars.

The loss of the "Third Place" has made this transition complete. A sociologist Ray Oldenburg coined the term for places that are neither work nor home: the pub, the library, the cheap cafe. These were the places where you bumped into people you didn't choose to know. Since the 2008 financial crisis, and accelerated by the pandemic, we have seen a mass disintegration of these places. Many shops have vanished, replaced by warehouses and delivery vans. We swapped the messy, inefficient, human interaction of the shop floor for the efficiency of "Buy Now".

We are left with an environment that is technically perfect and socially broken. We have neighbourhoods of high-rise apartments where thousands of people live stacked like reliable data storage units, sharing walls but never words. We have suburbs designed exclusively for the car, where walking is viewed as a sign of poverty, insanity, or the need to lose weight.

We didn't just drift apart, it was accidently engineered. We are the generation that remembers the "before times" and the generation that remembers the specific texture of a boredom that could only be cured by going outside to see who else was around. We are the ones who feel this loss of community the most. The question is no longer what happened. We know what happened. The question is whether we have the energy, the skepticism, and the sheer bloody-mindedness to reverse it.

Part II: What We Can Do as Individuals to improve community

The solution does not begin with a committee meeting. If there is one thing I think we all hate, it is forced participation in a group meeting, we have enough meetings in our life! We do not need more programs; we need to change our behaviour. We need to override the instincts that make us keep our heads down and doors shut.

We need to start doing these types of things:

- Stop thinking you are weird for talking. Stop thinking that if you talk to a person in the elevator, they will think you are a weirdo. People generally say they are happier on days they interact, even if they thought they would prefer to be alone. The person next to you is likely just as desperate for a human moment as you are; they are just waiting for you to blink first.

- Implement the 3-Second Rule. When you make eye contact with a neighbour, you have three seconds to acknowledge them before it gets weird. A nod, a wave, a smile. It doesn't have to be a conversation, it just has to be a signal that says, "I see you, and I am not a threat." If you are driving, wave before they do. Establish yourself as a friendly presence.

- Spend time in front of the house. Being visible is the easiest way to start the feeling of community. Try doing things at the front of your house, like drinking your coffee on the steps, fixing things in the driveway, or reading a book on a chair that is not behind a fence. By doing this you're showing people that the street is a place for living, not just for parking. You start to break down the home fortress.

- Be subtle about offering help. Be imaginative about how you can subtly tell your neighbours you are available to help. No one takes food around anymore, but maybe try dropping a card in a letterbox with your details and an invitation to reach out if they need help. The key here is that you don't need to become the extraverted crazy neighbour and that you just need to be present.

- Get over the fear of asking for things. Asking for a favour is actually a community-building act. When researching this article, I came across the "Ben Franklin Effect" It is a psychological phenomenon that feels backward in that we don’t just help the people we like and we eventually come to like the people we help. If you want someone to like you, the intuitive approach is to do a favour for them. However, this effect suggests the opposite is true, you should get them to do a favour for you. So when you ask someone to borrow a ladder or see if you can put something in their bin, you make them feel competent and needed. You turn them from a stranger into a helper. It breaks the ice.

- Garden on the verge. If you're the gardening type, you can use the verge by planting vegetables or native flowers on the strip of grass between the sidewalk and the road. It forces you to be out near the footpath. It invites comment. It turns a patch of government grass into a conversation starter.

- Stop doom-scrolling neighbourhood apps. Local Facebook groups have become toxic hellhole of paranoia and complaints. If you do engage, be the positive one and post about a fun event in the neighbourhood and not the teenager dangerously riding their bike (who was probably one of the few teenagers actually just riding home) or thank the person who planted the flowers. Refuse to engage in the hate.

Overall, you need to decide that the convenience of isolation isn't worth the cost of our humanity.

Part III: What Needs to Change at the Community Level

The reality is that you can wave at your neighbours until your arm falls off, but if the system is rigged against connection, you are pushing shit uphill. We need to look at the mechanics of our cities and the legislation that governs them. There are many boring bureaucratic things that are killing our communities, and we should fix them.

The biggest silent killer of community is Public Liability Insurance. It sounds dull, but it creates a reason for so many things to either not happen or become cost-prohibitive. If you try to organise a street party, a tool library, or a sausage sizzle today, you will be hit with an insurance bill that would make a corporate CEO weep. Risk aversion has gone mad. We have a litigious culture that has scared insurers out of the market.

We need some sort of indemnity or blanket insurance scheme. There should be a master policy that covers small, low-risk community events and limitations on the liability that can be claimed. If a neighbourhood wants to close a street for a party, insurance should not be required. We need to reform Liability Acts to acknowledge that if you fall over at playing a social kick around or trip over a beanbag at a block party, it is an accident, not a payday. We need to remove the risk of getting involved and being part of a community.

One place that does this well is New Zealand, where they keep local sport simple and cheap. In most places, you pay for every inch of grass. In NZ, you turn up, and pay say $5 to join a community game like touch football. No frills, turn up and away you go. In Australia, the price tag jumps to $18; most of that is due to insurance and the associated admin. You can't just turn up; you need to go through a complex registration process. The person organising it has lots of boxes to tick, and it becomes hard work. You’re playing the exact same game, but in Sydney, you’re paying more than triple what you’d drop in Auckland. The biggest issue is not the cost; it's the friction created to become part of a community activity rather than how it should be: low commitment and low difficulty.

Then there is the issue of where we live. Due to zoning laws, we seem locked into two choices: the condensed apartment neighbourhood, accentuated by high-rises, or the sprawling suburbs filled by McMansions. How about allowing more mixed zoning everywhere that allows for townhouses, duplexes, and terraces? The reality is that you can't have a local café, a corner shop, or decent transport if there aren't enough people within walking distance to keep things open. By doing this, we could up zone the suburbs so that "Third Places" are economically viable and there are enough types of places to make everyone welcome.

How about Superblocks, they have these in Barcelona. There they took nine city blocks and closed the internal streets to through traffic, turning them into pedestrian zones with picnic tables and playgrounds. Traffic goes around the outside, the inside is for living. Pollution dropped, noise dropped, and social interaction increased dramatically. We can do this, we just need the political will to take space away from cars and give it back to humans, and it will also help increase housing.

==finished here== One way we can start to get these things happening is to democratise the money. "Participatory Budgeting" is a concept that started in Brazil and is slowly creeping around the world. Instead of the council deciding how to spend every cent, a portion of the budget is given to the community to allocate. They decide if a new park bench is needed, or a mural, or a youth centre. It forces neighbours to negotiate and turns residents into active citizens.

While we are talking about community spending, we need to empower communities to protect and invest in their own local infrastructure. The UK has a "Right to Bid" law, which allows communities to pause the sale of a cherished asset—a pub, a library, a post office—to raise funds and buy it themselves. This idea could be expanded to include land so that when the last pub or green space in the community is being sold to developers to become condos, the community has the first right to make use of the land putting more power back into communities.

As the generation that has watched community slowly unravel. We have seen porches and streets empty and the screens light up. We were young when all this started to happened, but we now we sit in positions where we can help stitch it back together. I think the younger generations are keen to help too! We don't need and won't get a utopia. We just need neighbourhoods where it’s okay to knock on a door, where the street is safe enough to play a game, and where we aren't fined for trying to feed our neighbours.

We can have that. But we are going to have to walk outside and build it.